Growing public concern over climate change is pushing investors to increasingly assess how their portfolios are pivoting to a low carbon economy. Because of its large carbon footprint, the coal industry is a prime target of environmental activism and divestment campaigns, and it is becoming the investable hot potato few want to hold.

In this article, we sample the pros and cons of divestment campaigns, outline key risks and opportunities for investors and companies, and provide global examples of alternative approaches.

In recent years, large miners have divested coal assets while several insurers and banks around the world have pledged not to underwrite or finance coal related activities. Some investors have practiced coal exclusion rules for many years, while others continue to swell the ranks. The most recent investor to add coal to its sin list was BlackRock,[i] who in January 2020 announced that its USD 1.8 trillion actively managed assets would halt investing in companies that derive more than 25% of revenues from thermal coal extraction.

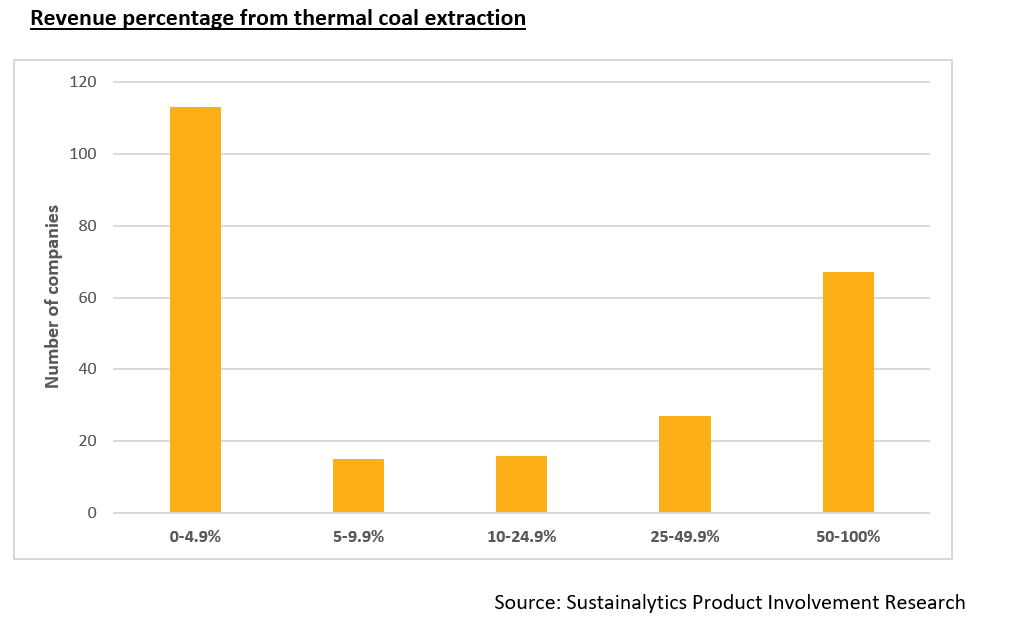

Sustainalytics’ Product Involvement research identifies 238 publicly listed companies (out of our coverage of 15,000) involved in thermal coal extraction. The chart below records only 94 companies that derive 25% or more of their revenues from coal production, removing them from potential investments in BlackRock’s actively managed portfolios. These companies produce the key input for coal-fired electric power generation plants that emit approximately 30% of total annual global GHG emissions.[ii]

Notable activities of large diversified miners with thermal coal assets

One of the earliest examples of miners divesting coal assets is Rio Tinto’s sale in 2016 of its Blair Athol mine in Queensland, Australia to the local miner TerraCom for just one dollar, [iii] enroute to Rio’s complete exit from coal mining 2018, raising USD 5.4 billion in the process.[iv]

In 2019, South32 announced the sale of its South African coal assets to Seriti Resources for USD 6.75 million, recognizing an impairment charge of USD 500 million. The terms of the sale accounted for the risk of sustained low coal prices (see below), but also contained a clause that South32 will receive 49% of the cash generated by the business until 2024.[v]

Not all deals have resulted in a loss though: Anglo American recognized a gain on the 2016 sale of its Callide mine in Australia to Batchfire Resources[vi]; in 2018, it recognized a USD 84 million gain from its USD 164 million sale of Eskom-tied coal asset in South Africa, also to Seriti.[vii]

In February 2019, Glencore committed to cap its global coal output, [viii] while BHP is considering selling its remaining coal operations.[ix] Japanese companies have also divested their interests in coal mines: in 2019, trading company Sojitz sold its 30% interest in an Indonesian mine, [x] and Mitsubishi Corp sold its USD 540 million stake in two Australian mines.[xi]

Comparing risks and rewards

The common corporate pitch of ‘strategic portfolio revisions to strengthen balance sheets’ signal that financial motivations, rather than environmental concerns, are the primary drivers of these actions: the selling companies have done the math (likely using carbon pricing), and do not see a viable future for the commodity. Our analysis highlights these key benefits:

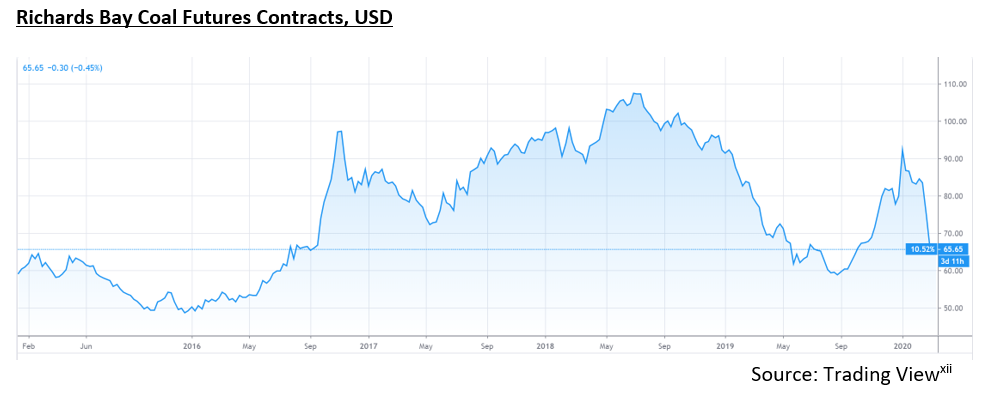

- Managing expectations over price and demand. As shown in the chart below, thermal coal prices have been volatile in the past five years. Future demand for coal is expected to come largely from Asia, but dampened by increase in regional production. With the global growth in renewables and impacts of carbon pricing on coal demand, thermal coal prices are expected to remain sticky out to 2024. Few people are betting on high prices for thermal coal in the future.

- Shedding of onerous supply contracts and liabilities. Companies may be locked into sale agreements where the price they receive for coal is lower than the cost incurred to supply it. In the abovementioned deal, Anglo American derecognized a USD 525 million provision for onerous contracts. Meanwhile, divesting a mine often means the seller is no longer responsible for its rehabilitation which can cost tens or hundreds of millions of dollars and can cause trouble if not conducted properly. It also shields the company from potential expenses of employee layoff packages.

- Improved access to capital. Divestments generate cash and free up capital that can be returned to shareholders or re-allocated for strategic portfolio acquisitions that better meet future demand forecasts. Promoting a ‘greener’ image can also be beneficial given the pledges in the financial sector mentioned above. A coal-free miner may benefit from decreased costs associated with its banking, credit and insurance needs, while appealing to a wider investor pool.

The benefits are not without potential downsides, such as:

- Weaker sustainability awareness of the buyer. Notwithstanding the financial reasons for selling, a miner exiting coal demonstrates awareness of environmental issues and responsiveness to stakeholder concerns. The acquiring company is arguably less attuned to sustainability trends and may have less robust ESG risk management practices embedded in its operations.

- Mine rehabilitation issues/concerns. Several of the buying companies are small size miners with weaker financial positions, calling into question whether they will be able to cover rehabilitation costs of the mines if coal price remains depressed. The sales of both Rio Tinto’s Blair Athol mine and Anglo American’s Callide have raised concerns about whether the buyers have sufficient funds for closure and rehabilitation when time comes.[xiii] [xiv] Westmoreland Coal Company, which bought a coal mine in New Mexico from BHP in 2016, filed for bankruptcy in 2019 – one of five US coal companies to do so in 2019.[xv] The concern remains that taxpayers may end up paying for mine rehabilitation if coal prices affect the profitability of small companies. In contrast, BHP, Rio Tinto and Anglo American have strong financial positions to cover environmental liabilities regardless of commodity prices.

- Buyers from disadvantaged groups. Some of the coal asset sales have been to marginalised and previously disadvantaged groups. For example, Seriti Resource, which bought mines from South32 and Anglo American, is a South African Black owned business. The Navajo Transitional Energy Company (NTEC), an entity of the Navajo Nation in the US, bought coal mines from BHP in 2013 and from Cloud Peak energy in 2019, after the latter declared bankruptcy. Coincidentally, Cloud Peak was a business unit that Rio Tinto spun off in 2009. The Navajo Nation is now concerned about being responsible for the rehabilitation liabilities of these mines. In the context of a ‘just transition’ that does not leave people behind, the sale of coal assets to companies owned by Indigenous people or historically disadvantaged groups raises ethical questions. These businesses and communities may be left with stranded assets and high environmental liabilities.

Passing the buck?

Granted, getting these assets off the balance sheet makes business sense for large diversified miners. However, even if the sale process is conducted responsibly and the acquirer can afford the rehabilitation costs, no net positive environmental impact has been achieved by selling the assets, rather than closing them altogether. Someone will still dig out that coal, and someone else will burn it.

Similarly, divesting coal stocks from a portfolio, or not underwriting or financing coal projects, may mean just passing the buck to someone else. In theory if an increasing number of investors will not buy coal miners’ shares, companies will not have access to capital at reasonable rates and stock prices will plummet. If banks and insurers pull the plug enabling services such as insurance and lending, coal companies cannot operate and need to close shop.

But these knock down effects are all but guaranteed. For any firm that distances itself from coal, there may be another willing to do business, and political support remains for the coal industry because “it provides jobs” – the Australian 2019 election and Adani’s Carmichael mine are illustrative case studies of precisely this. The important commitments and steps by investors and miners to walk away from coal are necessary, but divestment alone may take too long to make a meaningful difference. Additionally, cutting a financial relationship means losing leverage to influence change, engage with management, and vote.

Going beyond divestment

There needs to be a better plan, a better narrative and a better way forward to deal with coal.

A possible alternative approach comes from Genex Power, which converted an abandoned gold mine in Australia into a pumped hydro project, giving a second life to a mothballed asset and maintaining economic activity around it.[xvi] Similar projects are in early stages in the US to turn old coal mines into solar farms.[xvii]

The Powering Past Coal Alliance is a kind of ‘non-proliferation treaty’ initiative that brings together 100 national and local governments, businesses and organisations to accelerate phase out of coal power by 2030.[xviii] Canada, one of the founding members of the initiative, is supporting the transition to clean electricity by investing billions in strategic infrastructure and renewables while assisting affected coal workers and communities.[xix] In the process, the government expects USD 4 billion in environmental and health benefits from coal phase out.

Germany has taken bolder steps and may be showing a novel path forward. Following major negotiations and an unprecedented compromise between politicians, unions and businesses, the country announced a USD 45 billion package to shut down the coal industry by 2038. It involves compensating companies, workers and regions for economics losses, while heavily investing in renewable energy, restoration of ecosystems and biodiversity, and retraining of workers – a win-win for the environment and the economy in the long run. [xx] [xxi]

Many see this as an example that Australia and other countries could follow to move from an obsolete industry into a clean energy future. Divestments from mining companies and investors alone may not be enough to roll back climate change but integrated with government programmes, a timely solution is more achievable.

[i] https://www.blackrock.com/au/individual/blackrock-client-letter

[ii] https://www.iea.org/reports/global-energy-co2-status-report-2019/emissions

[iii] https://www.reuters.com/article/terracom-rio-tinto-idUSL4N19Q1YI

[iv] https://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-03-28/rio-tinto-sells-last-coal-mine-kestrel/9597352

[v] https://www.south32.net/docs/default-source/exchange-releases/agreement-to-divest-south-africa-energy-coal.pdf?sfvrsn=389b98f8_2

[vi] https://www.angloamerican.com/media/press-releases/2016/31-10-2016

[vii] https://www.angloamerican.com/media/press-releases/2018/01-03-2018

[viii] https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-02-20/glencore-moves-to-cap-global-coal-output-post-investor-pressure/10831154

[ix] https://www.smh.com.au/business/companies/bhp-boss-weighs-thermal-coal-exit-if-the-price-is-right-20200218-p541tg.html

[x] https://www.mining.com/web/japans-sojitz-sell-stake-indonesias-thermal-coal-mine/3328/

[xi] https://www.reuters.com/article/us-mitsubishi-coal-glencore/mitsubishi-exits-thermal-coal-sector-sells-stakes-in-australia-mines-idUSKBN1OH0QK

[xii] https://www.tradingview.com/symbols/ICEEUR-AFR1!/

[xiii] https://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-01-24/blair-athol-company-given-millions-in-surplus-enviro-funding/9353802

[xiv] https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2016/jan/29/coal-giants-abandon-unprofitable-mines-leaving-rehabilitation-under-threat

[xv] https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2019/10/29/coal-giant-murray-energy-files-bankruptcy-coals-role-us-power-dwindles/

[xvi] https://www.genexpower.com.au/250mw-kidston-pumped-storage-hydro-project.html

[xvii] https://solarmagazine.com/switch-to-solar-at-coal-power-plants-and-mines-is-on/

[xviii] https://poweringpastcoal.org/

[xix] https://poweringpastcoal.org/profiles/canada-EN

[xx] https://www.reuters.com/article/us-climate-change-germany-coal/germany-adds-brown-coal-to-energy-exit-under-landmark-deal-idUSKBN1ZF0OS

[xxi] https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-02-18/australia-climate-how-germany-is-closing-down-its-coal-industry/11902884

Recent Content

Six Best Practices Followed by Industries Leading the Low Carbon Transition

In this article, we take a closer look at the leading industries under the Morningstar Sustainalytics Low Carbon Transition Rating (LCTR) and examine the best practices that have allowed them to emerge as leaders in managing their climate risk.

Navigating the EU Regulation on Deforestation-Free Products: 5 Key EUDR Questions Answered About Company Readiness and Investor Risk

The EUDR comes into effect in December 2024, marking an important step in tackling deforestation. In this article, we answer five key questions who the EUDR applies to, how companies are meeting the requirements, and the risks non-compliance poses to both companies and investors

-5-key-questions-answered-about-company-readiness-and-investor-risk.tmb-thumbnl_rc.jpg?Culture=en&sfvrsn=ee2857a6_2)