In September 2023, the Corporate Accountability Lab published a report revealing child labor on cocoa farms supplying major packaged food companies like Barry Callebaut, Nestlé, Mars, and Ferrero. The research found that children performed hazardous work, earning less than the World Bank’s poverty threshold.1 This ongoing exploitation keeps children from attending school and prevents them from developing their capabilities, trapping them in a vicious cycle of generational poverty and systemic oppression. To address this and other societal and environmental issues the United Nations's adopted 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) almost a decade ago in 2015. Goal number eight of the SDGs — Decent Work and Economic Growth — includes a target to eradicate forced labor as well as all forms of child labor.2

Morningstar Sustainalytics recorded 612 human rights incidents related to food supply chains between January 2014 and January 2024, 27% of which were incidents of child labor on cocoa farms.3 Child labor has been prevalent in cocoa supply chains for decades and companies are aware of the issue. Yet, according to the International Labour Organization, work is “well off track” to reach the United Nations’ SDG target 8.7 to “end child labor in all its forms” by 2025.4 Using data from Sustainalytics’ ESG Risk Ratings, this article assesses how seven major cocoa industry players are falling short of effectively managing child labor in their supply chains, and offers ways investors can engage with companies to mitigate the issues.

The Economics of Cocoa: Systemic Reasons for the Persistence of Child Labor

The cocoa value chain is complex. Approximately five to six million smallholder farms under five hectares in size produce 90% of the global cocoa supply.5 Two countries, Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire, account for around 60% of global cocoa production.6 Farmers sell cocoa beans to aggregators, who gather them in volume from multiple regions to sell to traders and exchanges, before they are acquired by processors. Ground beans are then sold to manufacturers, brands, and retailers, who face the challenge of tracing the commodity back to its plantation of origin.7

Downward pressure on prices and fluctuating demand leaves cocoa farmers vulnerable to an unstable income.8 During the 1970s, cocoa farmers received 50% of the value of a chocolate bar. Today, however, that value has fallen to just 6%.9 Meanwhile, throughout 2023, chocolate prices rose by 14%.10 Nevertheless, an average cocoa farmer in Ghana and the Côte d’Ivoire earns 40% of a living income, which is the local minimum income needed to cover a household’s basic needs. This economic instability forces many smallholders to rely on children to work on their family farms in times of high demand.11

Child workers are vulnerable to unregulated work, with no social security or other safety nets. Children in the cocoa supply chain are often subject to hazards such as carrying heavy loads, exposure to pesticides, operating dangerous equipment, as well as long working hours and low pay.12 These are among the worst forms of child labor and are prohibited under international law.13

Despite many companies making public commitments to eliminate child labor, an estimated 45% of children living in cocoa growing areas continue to engage in farming activities. At the same time, demand for cocoa is growing rapidly. Chocolate companies are projected to generate USD263 billion in revenue by 2030, compared to USD206 billion in 2022.14

Assessing Companies’ Supply Chain Management Efforts, Trends and Gaps

Companies continue to come under scrutiny for their failure to meaningfully address child labor issues within their supply chains. Sustainalytics’ controversy research shows that over the last 10 years, 167 human rights incidents in food companies’ supply chains involved child labor in cocoa farming – 38% of which were recorded in the last three years.15 These incidents mostly relate to the continued use of child labor in the supply chains of seven major cocoa industry players: cocoa traders OFI Group Ltd. and Cargill, Inc., and chocolate manufactures Nestlé SA, The Hershey Co., Barry Callebaut AG, Mondelēz International Inc., and Chocoladefabriken Lindt & Sprüngli.16

While these companies continue to be involved in significant controversies related to child labor, they are not ignoring the issue and have responded to the long history of allegations through a focus on management efforts. The seven food companies being evaluated in this article scored well on the indicator assessing their policy commitments to ensure the observance of human rights among their suppliers (i.e., scope of supplier standards). Furthermore, the companies have strong supply chain management programs in place. However, despite overall strong management of the issues, meaningful gaps remain.

Not All Companies Address Minimum Living Wages

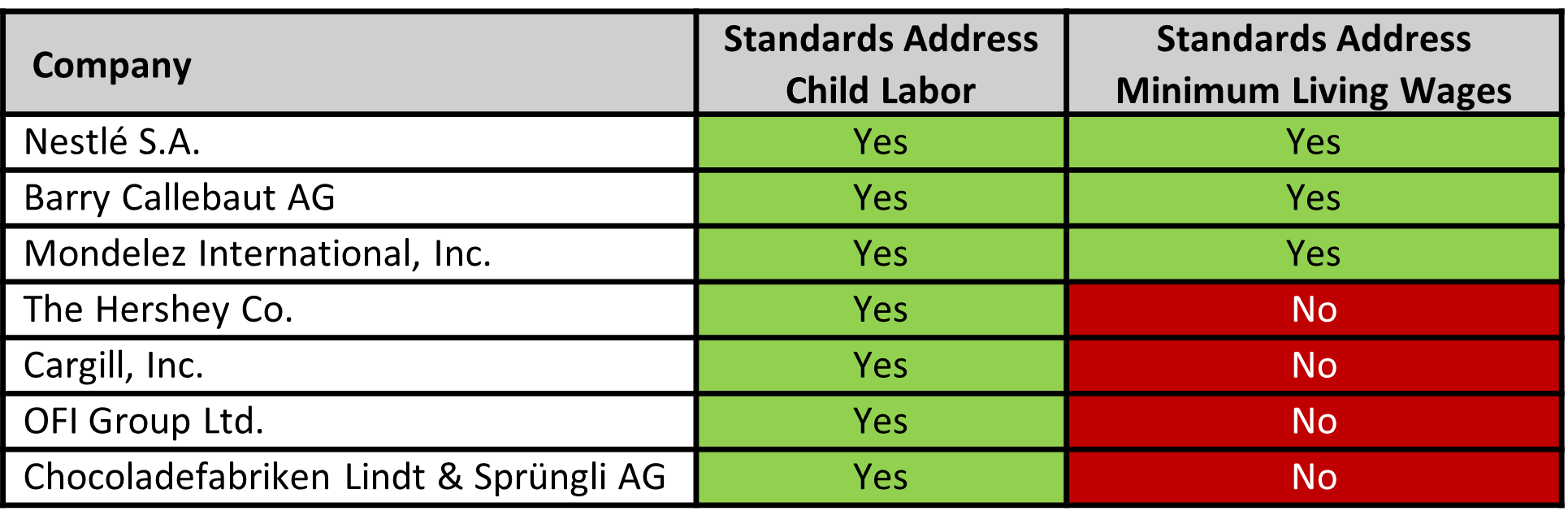

All seven companies in this assessment have a policy addressing child labor. However, only three have policies that address minimum living wages (see Table 1). Without a minimum living wage, cocoa farmers may experience unstable and insufficient income where they need to rely on their children to work on farms.

Table 1. Major Cocoa Industry Players Meeting Child Labor and Living Wage Criteria Within Their Scope of Supplier Standards

Source: Morningstar Sustainalytics. For informational purposes only.

Supply Chain Management Programs Are Not Applied to Their Entire Value Chain

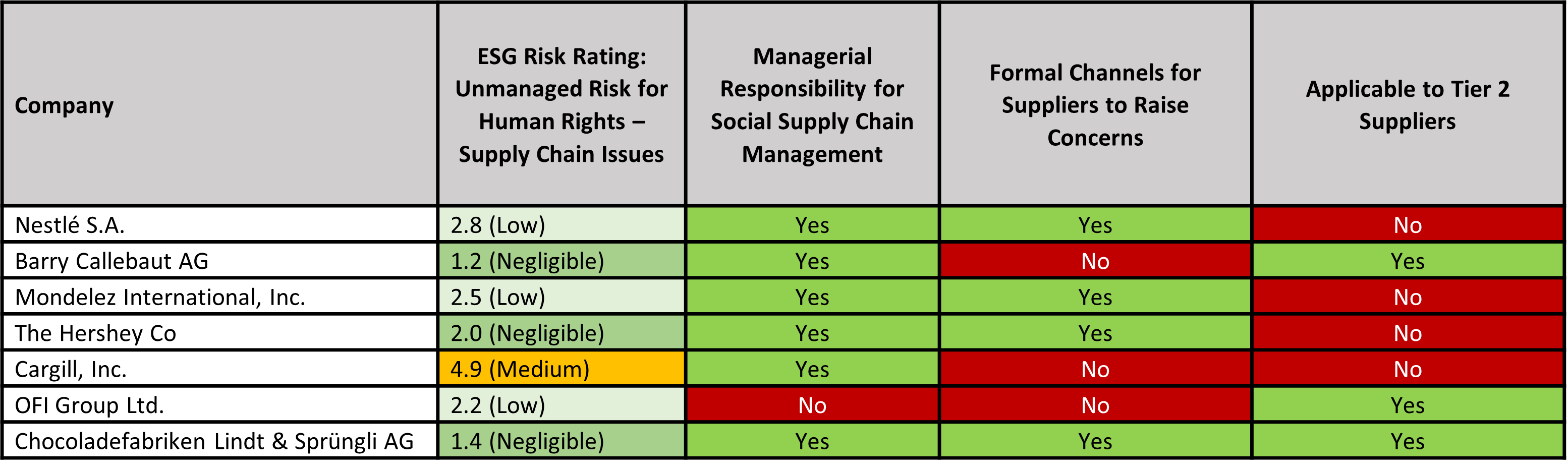

While most of the companies being assessed have managerial responsibility for social supply chain management, only four have formal channels in place for supply chain workers to raise concerns (see Table 2). Moreover, only four of the seven supply chain management programs are applicable to second-tier suppliers, with the remainder limited to first-tier suppliers.

Best practices in supply chain management include tracing cocoa back to its plantation of origin for both direct and indirect suppliers. However, this has proven to be a challenge for manufacturers due to the complexity of supply chains and the lack of plantation-level data. For example, Cargill only traces 10% of its indirect cocoa suppliers back to the point of purchase.17

Table 2. Major Cocoa Industry Players Meeting Specific Criteria Within Their Supply Chain Management Program

Source: Morningstar Sustainalytics. For informational purposes only.

Companies Are Implementing Leading Monitoring Standards, but Their Scope Is Still Limited

In recent years, the seven companies in this assessment have begun implementing Child Labor Monitoring and Remediation Systems (CLMRS) in response to allegations of child labor in their supply chains. The CLMRS is the leading method to monitor and remediate confirmed cases of child labor. Data has shown that, when executed properly, implementing a CLMRS can reduce child labor by over 50% over a three-year period.18 The concept of CLMRS is relatively new and most companies that have implemented one are currently expanding its scope. While zero tolerance approaches to child labor could push exploitation underground and result in some young workers taking up less regulated work in the informal sector, a CLMRS aims to keep the issue at the surface by working with farmers on the ground to provide child-centered solutions.

Despite the adoption of leading supply chain management practices, the companies assessed continue to be linked to alleged child labor violations. In January 2024, a Switzerland-based news program reported cases of child labor among Ghanaian cocoa farmers allegedly linked to Lindt’s supply chains.19 And in September 2023, a Brazilian labor court in Bahía ordered Cargill to perform human rights due diligence on its supply chain and pay a fine of BRL600,000 (USD120,185) as a penalty for buying cocoa from farms that used child labor.20

Understanding Company and Investor Risk

Investors face several risks associated with companies’ failure to adequately prevent and mitigate child labor in their supply chains.

Companies Face Legal Risks

Being subject to litigation is associated with legal fees and reputational costs, which can be exacerbated by a negative outcome. In December 2023, Terry Collingsworth, lead counsel at International Rights Advocates, representing activists, filed a lawsuit against Mars, Cargill and Mondelēz in the Superior Court of the District of Columbia. The lawsuit claimed the companies bought cocoa from West African farms that forced children to work on plantations. It also alleged the companies failed to take sufficient action to reduce the use of child labor in their supply chains and failed to address the ongoing issues on their plantations. The lawsuit sought to represent all affected child workers in Ghana’s cocoa industry. Mondelēz did not comment on the case.21

Media Attention Could Bring Reputational Risks

Consumers and shareholders are increasingly aware of human rights issues. The topic has been reported on by several major news outlets and has been the subject of several televised investigative reports.22 23 24 As of February 2024, over 29,000 consumers have signed a petition to hold corporations accountable for child labor in the cocoa industry.25 Retaining customers is essential to consumer goods companies and negative publicity can affect a company’s bottom line.

Regulatory Risks Are Rising

Internationally, there has been an increase in regulations related to corporate due diligence. For instance, the adoption of the European Union’s regulation on deforestation-free products will see governments holding corporations accountable for human rights violations occurring in their supply chains. The new regulation also includes financial penalties for non-compliance, exposing companies to regulatory and financial risk.26 Courts in other jurisdictions, such as Brazil, are also levying fines against companies for child labor violations in their supply chains.27 With a rise in human rights due diligence regulations, companies are exposed to an increasingly high risk of fines.

Driving Change in the Cocoa Industry Through Meaningful Investor Engagement

As awareness spreads, some investors have begun engaging companies on the issue of child labor in cocoa value chains. For instance, shareholder organization Tulipshare with a voting power of USD620 billion, together with Advance ESG, filed a resolution requesting that Mondelēz International’s board of directors eliminate child labor from its cocoa supply chains by 2025 and comply with SDG8.7.28

A more holistic understanding of this complex issue combined with identifying companies’ remaining management gaps can guide meaningful engagement dialogues between investors and companies. We recommend centering engagement around three key topics:

- Minimum Living Wage

- Scope of Supply Chain Management Policies

- Monitoring and Remediation Processes

Although companies have strong supplier standards on child labor, there are gaps when it comes to addressing the related issue of minimum living wages. Ensuring that suppliers pay companies a living wage can reduce farmers’ reliance on the labor of family members, including children. These wages need to be revisited on a regular basis to ensure they are adjusted to inflation and cover the local cost of living.

Tracing cocoa back to the plantation level remains a challenge. However, to effectively prevent child labor, companies need to extend the scope of their supply chain management beyond first-tier suppliers to get to the root of the issue.

Companies need to monitor and remediate confirmed cases of child labor. Child-sensitive grievance mechanisms should include non-retaliation clauses and be made accessible to children by removing physical, communication and economic barriers.29

Confirmed cases of child labor must be remediated in collaboration with local governments and civil society organizations to follow up with children for at least three years to ensure they remain enrolled in schools and stay out of child labor. Investors can engage companies by following up on progress and asking what CLMRS key performance indicators are being tracked. Remediation efforts should be based on individual needs and can range from providing school supplies to ensuring a living wage is paid to smallholder farmers.

Although we are still far from ending child labor in all forms, the trend of companies implementing a CLMRS is a positive development. As a next step, companies need to extend the scope of their prevention and remediation efforts to reach more children. Involving different actors through value chain engagement is a powerful tool for investors to foster a sense of accountability and influence positive change within companies.

References:

- Corporate Accountability Lab. 2023. “’There will be no more cocoa here.’ How companies are extracting the West African Cocoa Sector to death.” https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5810dda3e3df28ce37b58357/t/6515a2e3206855235dcb3c5a/1695916782152/There+Will+Be+No+More+Cocoa+Here+-+Final+Engligh.pdf.

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Sustainable Development. Sustainable Development. 2023. “The 17 Goals!. Accessed 9 February 2023. https://sdgs.un.org/goals.

- Data is according to Morningstar Sustainalytics Ratings universe, which comprises approximately 5,000 large and medium market cap investable issuers in developed and emerging markets.

- International Labour Organization. 2023. “Policy Brief: Sustainable Development, Decent Work and Social Justice An update on progress towards SDG 8.” ILO. 20 April 2023. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---exrel/documents/publication/wcms_894246.pdf.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- OECD. 2023. “Business Handbook on Due Diligence in the Cocoa Sector: Addressing Child Labour and Forced Labour”. OECD Publishing. 28 April 2023. https://doi.org/10.1787/79812d6f-en.

- Dawidowski Widstrand, C., Gaber, F. 2021. “AP 7 Theme Report. Working Conditions in Food Supply Chains.” AP7. 11 October 2021. https://www.ap7.se/app/uploads/2021/10/ap7-theme-report-working-conditions-in-food-supply-chains.pdf.

- Gaffar, C, Kämpfer, I., The Centre for Child Rights and Business. 2023. “Child Rights Risks in Global Supply Chains: Why a ‘Zero Tolerance’ Approach is not Enough.” Save the Children Deutschland e.V. 9 May 2023. https://www.cocoainitiative.org/sites/default/files/resources/save-the-children-child-rights-risks-in-global-supply-chains-2023.pdf.

- Ying Shan, L. 2023. “Chocolate is set to get more expensive as cocoa prices soar to seven-year highs.” CNBC. 12 June 2023. https://www.cnbc.com/2023/06/13/chocolate-is-set-to-get-more-expensive-as-cocoa-prices-soar-to-seven-year-highs.html.

- Nilsson, S. 2022. “Leading Companies Increasingly Want Farmers Paid a Living Income.” World Cocoa Foundation. 4 April 2022. https://www.worldcocoafoundation.org/blog/leading-companies-increasingly-want-farmers-paid-a-living-income/.

- Ibid. Ying Shan, L. 2023.

- International Labour Organization. 1999. “C182 - Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention, 1999 (No. 182).” ILO. 17 June 1999. https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::P12100_ILO_CODE:C182.

- Ibid. Corporate Accountability Lab. 2023.

- Data is according to Morningstar Sustainalytics Ratings universe, which comprises approximately 5,000 large and medium market cap investable issuers in developed and emerging markets.

- Information about these incidents was gathered from NGO reports, media allegations, lawsuits, petitions and investigations.

- Cargill. 2022. “Cocoa and Chocolate Sustainability Progress Report 2021”. Cargill. 15 June 2022. https://www.cargill.com/doc/1432213708736/cargill-cocoa-sustainability-progress-report-2021.pdf.

- International Cocoa Initiative. 2017. “New report highlights Nestlé’s efforts to tackle child labour in its cocoa supply chain”. ICI. 30 June 2017. https://www.cocoainitiative.org/news/new-report-highlights-nestles-efforts-tackle-child-labour-its-cocoa-supply-chain.

- Swissinfo. 2024. “Children work in Swiss chocolate maker Lindt’s supply chain in Ghana.” Swissinfo. 25 January 2024. https://www.swissinfo.ch/eng/business/child-laber-in-africa-chocolate-maker-lindt-s-supply-chain-in-ghana-scandal/49147288.

- Texeira, M., Mano, A. 2023. “Brazil court finds Cargill in case involving child labor on cocoa farms.” Reuters. 27 September 2023. https://www.reuters.com/world/americas/brazil-court-fines-cargill-case-involving-child-labor-cocoa-farms-2023-09-26/.

- Patta, D., Cater, S., Guzman, J, Breen, K. 2023. “Candy company Mars uses cocoa harvested by kids as young as 5 in Ghana: CBS News investigation.” CBS News. 29 November 2023. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/children-harvesting-cocoa-used-by-major-corporations-ghana/.

- Whoriskey, P. 2020. “U.S. report: much of the world’s chocolate supply relies on more than 1 million child workers.” The Washington Post. 19 October 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2020/10/19/million-child-laborers-chocolate-supply/.

- Patta, D. 2023. “Iconic chocolate brand linked to child labor in Ghana.” CBS News. 1 December 2023. https://www.cbsnews.com/video/iconic-chocolate-brand-linked-to-child-labor-in-ghana/.

- The Guardian. 2023. “John Oliver on child labor in the chocolate industry: ‘It is worse than you may realize’”. The Guardian. 30 October 2023. https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2023/oct/30/john-oliver-last-week-tonight-chocolate-industry-child-labor.

- Change.org. September 24, 2023. “Help Take a Stand Against Child Labor in Cocoa Factories.” https://www.change.org/p/help-take-a-stand-against-child-labor-in-cocoa-factories.

- European Union. 2023. “Regulation (EU) 2023/1115 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 31 May 2023 on the making available on the Union market and the export from the Union of certain commodities and products associated with deforestation and forest degradation and repealing Regulation (EU) No 995/2010”. EU. June 09, 2023. http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2023/1115/oj.

- Ibid. Texeira, M., Mano, A. 2023.

- AdvanceESG. 2022. “Mondelez.” 7 December 2022. https://www.advanceesg.org/projects/shareholder-resolutions/mondelez/.

- Unicef. January 28, 2019. “Child-Friendly Complaint Mechanisms”. https://www.unicef.org/eca/sites/unicef.org.eca/files/2019-02/NHRI_ComplaintMechanisms.pdf.

.tmb-thumbnl_rc.png?Culture=en&sfvrsn=12471767_1)