Last year, US lawmakers introduced the bipartisan Diversifying Investigations Via Equitable Research Studies for Everyone (DIVERSE) Trials Act and the Diverse and Equitable Participation in Clinical Trials (DEPICT) Act, both of which seek to improve diversity in clinical trials. Although clinical trials have become more diverse since the 1993 passage of the NIH Revitalization Act, which prompted guidelines on the inclusion of women and ethnic minorities, a vast gulf persists between the demographic makeup of wider society and clinical trial populations.1 This problem is caricatured in cardiovascular disease, where Black participants represented just 4% of enrolment for 35 novel cardiology drugs between 2008 and 2015. In contrast, Black individuals comprise 13.4% of the US population and are disproportionately likely to suffer from cardiovascular disease.2

Part of the issue stems from the inadequate collection of demographic data, a problem that the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted. Of 1,518 COVID-19 trials registered on the publicly accessible database ClinicalTrials.gov, just six collected ethnicity data, according to a November 2021 report.3 Without this data, it becomes exponentially more difficult to hold companies responsible and accurately measure clinical trial diversity.

Why Diversity in Clinical Trials Matter

A complex interplay exists between genetics, diet and (patho)physiology, which alters the interaction between patient and drug, causing variation in treatment responses between people.4 A lack of trial diversity can result in this variability going unnoticed, leading to inaccurate results. Low diversity increases the risk of unforeseen side effects, only discovered after the drug hits the market, exposing patients to harm and companies to litigation.

U.S. policymakers are now taking notice of clinical trial diversity and are prioritizing it in the legislative agenda. The DEPICT Act gives the U.S. Food and Drug Administration the authority to instruct companies to carry out post-market studies on the grounds of low diversity,5 which should help ensure that efficacy and safety data is collected across ethnic groups. Meanwhile, proponents of decentralized or virtual trials have argued that these will increase diversity by reducing travel and time costs. However, access to mobile technology remains a barrier. The DIVERSE Trial Act allows biopharma companies to provide participants with the necessary mobile technology, thus ensuring that access to trials is not restricted by socio-economic status.6 These acts highlight the growing role of government intervention and regulatory scrutiny in the pharmaceutical market.

Assessing Management of Clinical Trial ESG Risks and Opportunities

Given the variability in treatment efficacy and safety, clinical trial diversity could indicate long-term success in the pharmaceutical industry. Companies that maximize subpopulations in clinical trials can identify in which groups their products stand to outperform while saving resources where their clinical assets may fail to penetrate the market. This could significantly increase companies’ exposure to the rise of precision medicine, which is at the forefront of healthcare innovation. Furthermore, increased clinical trial diversity should enable companies to better identify safety issues for certain populations prior to market entry, in turn limiting the financial and legal risk associated with product recalls and patient litigation.

Sustainalytics’ ESG Risk Ratings provides insights into the strength of a company’s approach to clinical research. Two indicators in the Business Ethics Material ESG Issue (MEI), Clinical Trial Standards and Clinical Trial Program, assess a company’s policy and program for ensuring that ethical standards are respected during clinical trials.

The Clinical Trial Standards indicator assesses a company’s policy for ensuring that clinical trials are conducted ethically. Meanwhile, the Clinical Trial Program indicator takes a more pragmatic perspective on a company’s actions and management practices regarding clinical research, focusing on employee awareness education and training, and evidence of an independent ethics committee with authority to approve, modify or stop trials.

We believe that firms with high scores on these two indicators are not only better equipped to mitigate increasing reputational and regulatory risks related to clinical trial diversity but may also reap financial rewards through reduced patient litigation and industry-leading precision therapeutics. This would positively affect another important MEI for both pharma and biotech companies: Product Governance.

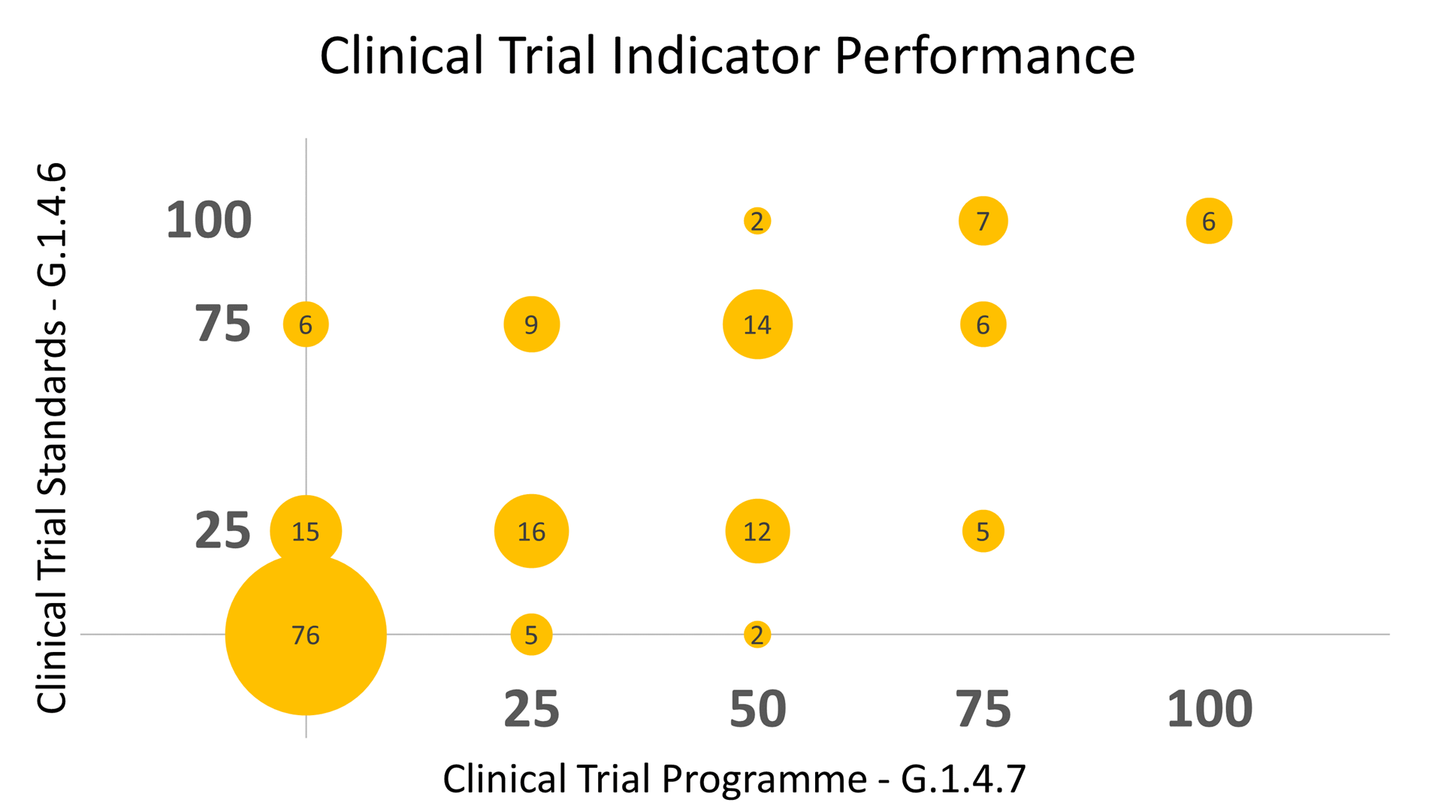

Figure 1: Clinical Trial Management Performance as Assessed Using Sustainalytics’ Clinical Trial Indicators

Numbers in bubbles indicate the number of companies that have achieved a given combination of scores

Source: Sustainalytics

As Figure 1 shows, only six out of 181 biopharma companies attained the highest score in both indicators, equivalent to just 3.3% of the total companies included in Sustainalytics’ ESG Risk Ratings universe. Meanwhile, 76 companies (over 40% of assessed companies) provide no evidence of clinical trial standards or a clinical trial program, indicating that they have ample room for improvement.

Now Is the Time to Prepare for Increasing ESG Risk

The benefits of clinical trial diversity are well documented. Yet, government intervention may be needed to push the industry in the right direction, given that 57% of biopharma companies lack a clinical trial policy and/or program. The forthcoming US legislation on trial diversity could therefore be a catalyst for positive change, though it will also bring new risks for companies that fail to adapt to the shifting landscape. Companies with clear and effective standards and programs for clinical trials will likely be best placed to mitigate the regulatory and compliance risk that accompanies state interference while profiting from the benefits of clinical trial diversity.

Contact our team to learn more about Sustainalytics' ESG Risk Ratings methodology and how it can be applied to your portfolio ESG risk assessments.

Sources:

1. Knepper, T.C. and McLeod, H.L., 2018. When will clinical trials finally reflect diversity?

2. Prasanna, A., Miller, H.N., Wu, Y., Peeler, A., Ogungbe, O., Plante, T.B. and Juraschek, S.P., 2021. Recruitment of Black adults into cardiovascular disease trials. Journal of the American Heart Association, 10(17), p.e021108.

3. Innovative Trials (2021), Ending the ‘Diversity Gap’ in Research. https://innovativetrials.com/press-release-ending-the-diversity-gap-in-research/

4.Ramamoorthy, A., Pacanowski, M.A., Bull, J. and Zhang, L., 2015. Racial/ethnic differences in drug disposition and response: review of recently approved drugs. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 97(3), pp.263-273.

5.Congress.Gov (2021), H.R.6584 DEPICT Act. https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/6584

6.Congress.Gov (2021), S.2706 DIVERSE Trials Act. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/BILLS-117s2706is/pdf/BILLS-117s2706is.pdf