English version follows below.

Quand les nouvelles réglementations sur les investissements durables et responsables (ISR) furent annoncées avec le « EU Action Plan », les institutionnels français n'ont pas cillé. Depuis l'accord de Paris en 2015, de nombreuses nouvelles obligations réglementaires liées à la publication d’information et à l’analyse ESG ont influencé les stratégies d’investissements responsables des institutionnels français. Le règlement SFDR1 qui est entré en vigueur le 10 mars dernier vient s’ajouter au cadre réglementaire local en matière de reporting.

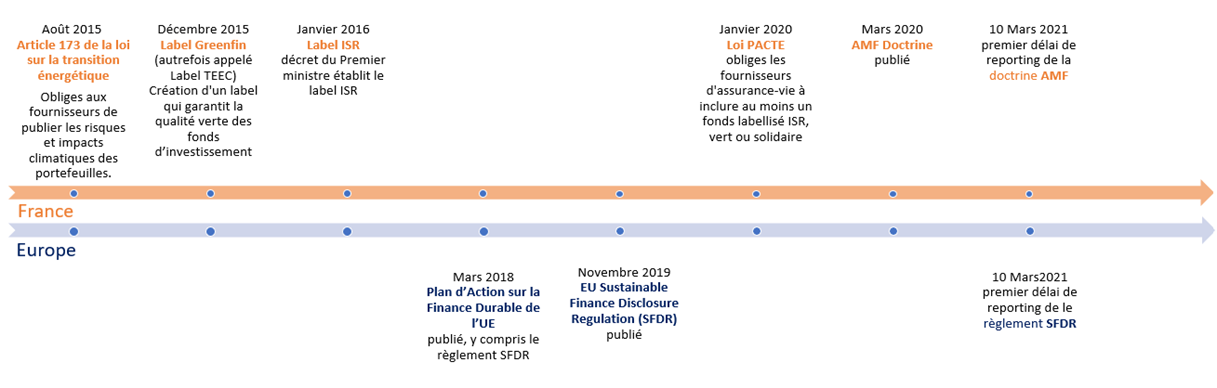

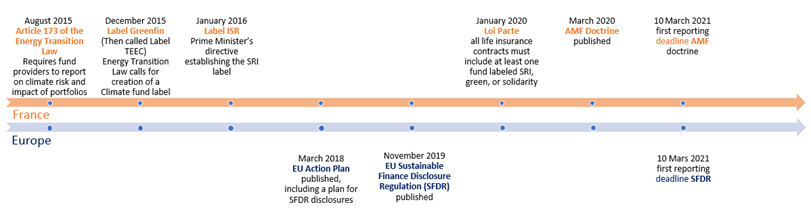

- L'article 173 de la loi sur la transition énergétique, promulguée en 2016, a été la première réglementation importante en matière d’évaluation et de publication des risques et impacts sur le changement climatique des investissements.

- Début 2020, la loi PACTE2 a imposé aux prestataires de produits d’assurance-vie l’intégration de fonds labellisés ISR dans leur offre.

- A suivi en mars 2020, la publication par l'Autorité des Marchés Financiers (AMF) de sa « doctrine », qui fournit des recommandations sur l’adéquation entre le niveau d’engagement ISR des fonds et la communication vis-à-vis des clients.3

Figure 1: Chronologie des normes ISR en France et dans l'Union Européenne

Le calendrier de la conformité à la doctrine de l'AMF a commencé au même moment que le premier volet d’exigences de publication du règlement SFDR de l'UE. D'autres obligations d'information suivront, au fur et à mesure du déploiement du plan d'action européen pour la finance durable.

Points communs et divergences entre la Doctrine AMF et le règlement Disclosure :

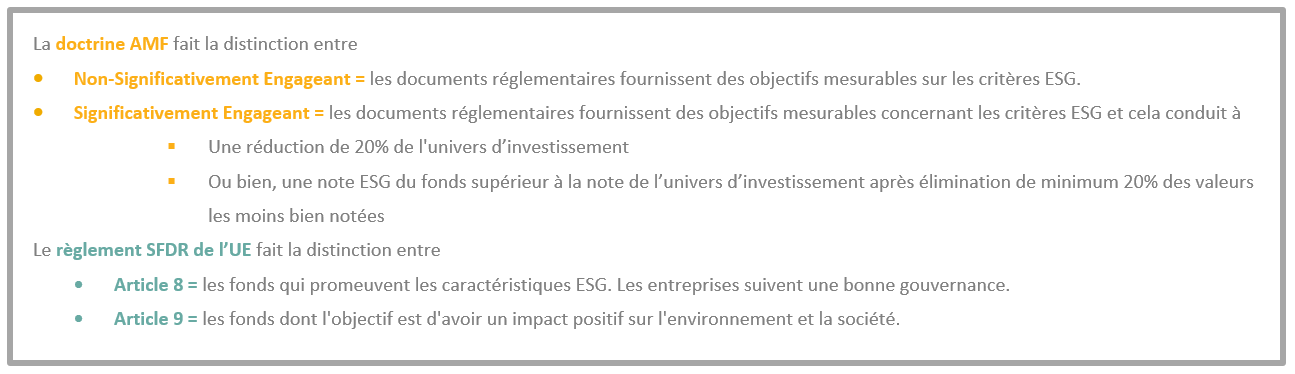

Bien que les régimes de reporting nouvellement imposés aux fonds ISR aient chacun leur singularité en termes de critères et de portée géographique, il existe néanmoins d'importantes similitudes :

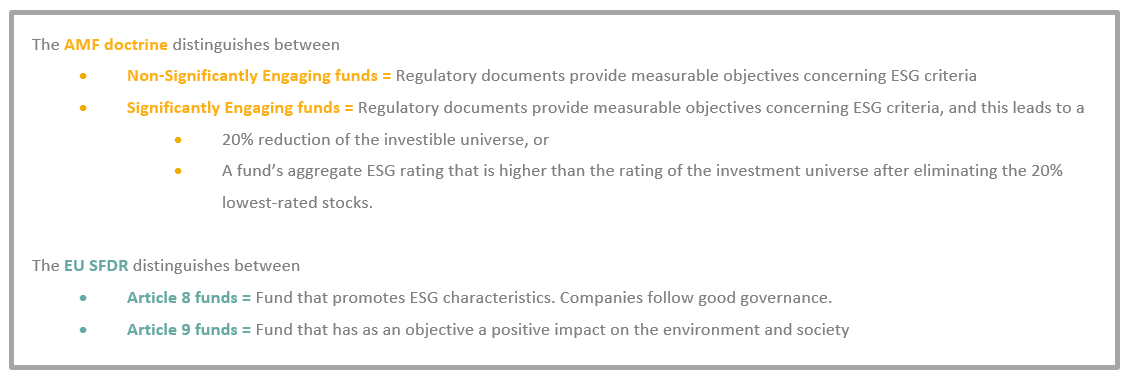

- La doctrine de l'AMF et la SFDR rattachent toutes deux les régimes de reporting à une catégorisation des engagements ESG des fonds.

- Toutes deux ont pour objectif de standardiser le reporting ESG.

- Toutes deux identifient deux catégories de fonds ISR et une catégorie de fonds non ISR.

En même temps, il existe des différences significatives dans la philosophie de la doctrine de l'AMF et du cadre de la SFDR.

- Périmètre d’investissement : La doctrine de l'AMF est plus prescriptive, étant donné qu'elle impose un seuil quantitatif pour la catégorie d'intégration ESG la plus élevée ; ainsi les fonds dans la catégorie la plus élevée (Significativement Engageant) doivent réduire de 20% leur univers d’investissement sur la base des critères ESG (ou bien, la note ESG du fond doit être supérieure à la note de l’univers d’investissement après élimination de minimum 20% des valeurs les moins bien notées). La SFDR, quant à elle, ne prévoit aucun seuil pour différencier les catégories de fonds ISR. Elle les catégorise plutôt en fonction de l'accent mis par la stratégie du fonds sur les caractéristiques ESG ou les objectifs durables.

- Objectif : Le règlement SFDR met l'accent sur la transparence tandis que la doctrine AMF vise à ce que la communication sur l'ISR soit proportionnelle au niveau d'intégration et d'engagement ESG.

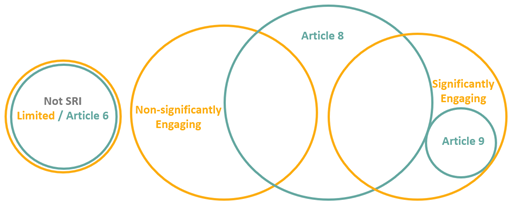

Figure 2: Superposition des classifications des fonds de l'AMF et la SFDR de l’UE, Source: Sustainalytics

Interprétation des catégories dans la communication sur les investissements

La catégorisation du SFDR a été créée principalement pour les sociétés de gestion d'actifs afin d'identifier en fonction du positionnement de chaque fond les exigences en matière de reporting et de communication vis-à-vis des clients. Elle n'aura donc qu'une utilité limitée pour aider les clients à filtrer les fonds en fonction de leurs critères d'investissement ESG spécifiques. Cette situation risque de devenir difficile, car de nombreux fonds ont déjà été classés dans la catégorie de fonds dit « article 8 ». Sachant le niveau limité d’exigence requis, nous nous attendons à ce que cette catégorie englobe une vaste gamme de stratégies.

Certains gestionnaires d'actifs risquent de considérer la catégorisation créée par ces deux règlements comme des opportunités de marketing pour positionner leurs fonds comme étant axés sur l'ESG. L'article 8 n'est pas destiné à être un sceau de qualité, mais il existe un risque que les gestionnaires d'actifs le traitent comme tel. De nombreux fonds pourraient ainsi être étiqueté « article 8 », d’autant que les gestionnaires d'actifs ne saisissent peut-être pas pleinement les obligations de reporting et de transparence qui seront imposées lorsque les exigences de niveau 2 du SFDR entreront en vigueur. Cependant, pour aider à filtrer ces fonds, on peut s'attendre à ce que l'application du double critère de l'article 8 et de la classification "Engagement significatif" de l'AMF contribue à plus de clarté. La combinaison de la doctrine plus prescriptive de l'AMF avec la SFDR pourrait aider les clients à identifier les fonds de l'article 8 qui sont significativement engageants (appliquant une restriction d'investissement) par rapport à ceux qui ne le sont pas.

Pourtant dans la pratique, les équipes de communication marketing n'exploitent pas autant la classification des fonds lié à la doctrine AMF que celle de la SFDR. Pour une utilisation comme critère de sélection, il faudrait une analyse détaillée par le client qui lui permette d’identifier la bonne catégorie de fonds. Actuellement, afin de démontrer la pertinence de l’appartenance de leurs fonds à la catégorie « Engagement significatif » de l'AMF, les gestionnaires s'appuient sur le label ISR pour démontrer la réalité de la réduction de leur périmètre d'investissement. De plus, la doctrine de l'AMF est essentiellement une réglementation locale qui n'aura que peu de sens dans un contexte pan-Européen ; on peut donc s'interroger sur son utilisation par les gestionnaires de fonds qui visent à distribuer leurs fonds à un niveau régional et mondial.

Ces nouvelles réglementations se recoupent et vont certainement accroître la transparence en matière d’ESG. L'investisseur final sera néanmoins confronté à une multitude d'informations sur les impacts de durabilité des investissements et le niveau de sélectivité ESG. Avec le niveau de détail et le nombre de données disponibles, on peut s'interroger sur la pertinence des labels de fonds ISR pour la prise de décision d'investissement à l'avenir. Il reste à voir si cette quantité accrue d'informations aidera les investisseurs individuels à évaluer la durabilité de leur investissement.

Nous vous invitons à venir écouter notre panel d’experts et de représentants de l’industrie échanger sur les enjeux à venir dans la mise en place de la SFDR.

Sources:

1. Le Plan d'Action pour la Croissance et la Transformation des Entreprises (PACTE)

2. Règlement SFDR (Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation) de l'UE

3. Autorité des Marchés Financiers. Informations à fournir par les placements collectifs intégrant des approches extra-financières.

//

The SRI Regulation Overlap of France and European SRI

Many France financial market participants did not flinch when the new regulations on Sustainable and Responsible Investments (SRI) were announced with the EU Action Plan. Since the Paris agreement in 2015, many new regulatory obligations related to ESG disclosures and research have influenced the responsible investments French institutional investors have made. The Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation that came into effect on 10 March 2021 adds to the existing reporting instructions by the local government.

- Article 173 of the Energy Transition law provided the first important disclosure regulation focused on climate risk and impact assessments of a fund’s portfolio since 2016.

- The PACTE law[1] includes a rule for pension fund and life insurance providers to incorporate SRI labeled funds in their offering.

- More recently, the Financial Market Authority (Autorité des Marchés Financiers) communicated their ‘doctrine’ in March 2020, which provides recommendations on how to communicate with customers on SRI funds based on the funds level of SRI commitments.

Figure 1: Timeline of SRI standards in France and EU, Source: Sustainalytics

The timeline for the AMF doctrine reporting coincided with the first part of the EU Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation[1] disclosure requirements. Additional disclosure requirements will follow as the broader EU Action Plan for Sustainable Finance rolls out.

Commonalities and discrepancies between AMF and SFDR:

While the newly imposed reporting regimes for SRI funds each have their own set of criteria and geographical scope, there are important similarities:

- Both the AMF doctrine and the SFDR attach reporting regimes to a categorization of ESG commitments.

- Both have the objective to standardize ESG reporting.

- Both identify two SRI fund categories and one non-SRI fund category.

At the same time, there are significant differences in the philosophy of the AMF doctrine and the SFDR framework.

- Investment Thresholds: The AMF is more prescriptive, given that it imposes a quantitative threshold for the highest ESG integration category. These funds should reduce their investible universe by 20% based on ESG criteria for the highest ESG category (or the ESG rating of the fund must be higher than the rating of the investment universe after eliminating the 20% lowest-rated stocks). The SFDR, on the other hand, does not provide any thresholds to differentiate SRI fund categories. Instead, it categorizes them based on the fund’s strategy’s focus on either ESG characteristics or sustainable objectives.

- Objective: The SFDR focuses on transparency, while the AMF doctrine aims to raise SRI communication to be proportionate to the level of ESG integration and commitment.

Figure 2: Overlapping fund classifications of the AMF and SFDR

Interpreting the categories in investment communication

The SFDR categorization has been created predominantly for asset management firms to identify their reporting requirements according to their funds positioning and client communication. Hence, it will have limited usability to help clients filter funds according to their ESG investment criteria. This situation is likely to become challenging as numerous funds have already been categorized as Article 8. funds. Acknowledging the limited number of required ESG commitments, we expect this category to capture a vast range of strategies.

Several asset managers might see the categorization created by these two regulations as marketing opportunities to position their funds as ESG focused. Article 8 is not intended to be a quality stamp, but there is a risk that asset managers will treat it as such. Many funds would qualify for Article 8 and “non-significantly engaging” categories as asset managers might not fully grasp the reporting and transparency requirements that will be mandatory once the level 2 requirements of the SFDR will come into effect. However, to help filter these funds, one can expect that applying the double criteria of Article 8 and the AMF’s Significantly Engaging classification will help clarify. Combining the more prescriptive AMF doctrine with SFDR might guide clients to identify Article 8 funds that are Significantly Engaging (applying investment restriction) versus those that are not.

However, in practice, marketing communication teams might not leverage the AMF doctrine fund classification compared to the SFDR classification. To be leveraged as selection criteria, the client would require a detailed analysis to identify the right fund categorization. Currently, the demonstration of the AMF’s ‘Significantly Engaging’ category relies on the France SRI label to demonstrate the reality of their investment perimeter reduction. In addition, the AMF doctrine is essentially a local regulation that will be meaningless in the EU context; therefore, one can question its usage by fund managers aim at distributing their funds on a regional and global level.

The new set of regulations overlap and will certainly increase ESG transparency. The end investor is faced with an increasing amount of information on the sustainability impacts of investments and the level of ESG selectivity. With the level of detail and data available, one can question the relevance of the SRI fund labels for investment decision making in the future. It remains to be seen whether this increased quantity of information will help end investors to assess sustainability quality.

Sources:

1. PACTE – Action Plan for Business Growth and Transformation

2. EU Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation

3. AMF. Information to be provided by collective investment schemes incorporating non-financial approaches.

.tmb-thumbnl_rc.png?Culture=en&sfvrsn=12471767_1)