Forced labor is often a hidden issue for investors and, given the complexity of global supply chains, it may also be hidden from companies.1 It is an issue that investors should not ignore as it presents financial, regulatory, and reputational risks to investee companies, alongside broader social impacts. In this article, I share how investors can assess companies’ understanding and management of forced labor risks.

Notable Forced Labor Regulations

The International Labour Organization (ILO) defines forced or compulsory labor as, “all work or service which is exacted from any person under threat of a penalty and for which the person has not offered himself or herself voluntarily.”2 There is some room for interpretation here, with certain terms, namely “work,” “penalty,” and “voluntary,” encompassing a relatively wide scope. The above definition was incorporated into the ILO’s 1930 Forced Labour Convention (No. 29),3 which states that forced labor should be punished as a crime. Later, in 1957, the Abolition of Forced Labour Convention (No. 105)4 was implemented to deal with state-imposed forms of forced labor.

More recently, regional efforts have been made to eradicate forced labor. In November 2024, the European Parliament approved the Forced Labour Regulation (FLR),5 banning products made with forced labor from the EU single market, which comprises mainly the 27 member states of the European Union.

In the UK, the Modern Slavery Act 20156 includes provisions about, “slavery, servitude and forced or compulsory labor and about human trafficking,” in accordance with Article 4 of the European Convention on Human Rights.

Elsewhere, in the US, there are several pieces of legislation relating to the identification, prevention, and mitigation of forced labor in supply chains. The United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA)7 contains a set of extensive labor provisions, and the U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) is responsible for preventing the entry of products made with forced labor; for example, by issuing Withold Release Orders (WRO)8 and enforcing the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (UFLPA).9 Some states have specific legislation, such as the California Transparency in Supply Chains Act, which requires companies to disclose their efforts in the following five areas relating to forced labor: verification, audits, certification, internal accountability, and training.10

Forced Labor Statistics

The ILO estimates that there are almost 28 million people in forced labor, with Asia and the Pacific host to more than half of this figure (15.1 million people).11 However, Arab states have the highest prevalence of forced labor when expressed as a proportion of the population (5.3 people in every thousand).12

Approximately 87% of forced labor occurs in the private sector, predominantly in services, manufacturing, construction, agriculture, and domestic work.13 In 2023, the Walk Free Foundation estimated that the value of goods at risk of being associated with modern slavery in G20 countries was USD 468 billion.14 The US Department of Labor also provides a list of goods and their source countries at high risk of being produced with forced or child labor.15

Given the inherent difficulties in accurately measuring outcome indicators for forced labor, investors should focus on robust leading indicators during their evaluations. Leading indicators can provide critical insights into a company’s performance and ability to mitigate forced labor risks. This, in turn, enables more informed and responsible investment decisions.

Why Forced Labor Matters to Institutional Investors

Institutional investors constantly look to mitigate and eliminate avoidable risks, and forced labor within an investee’s supply chain presents significant operational, regulatory, and reputational risks. Despite assumptions that forced labor could yield economic benefits, a growing body of research reveals that it can lead to severe productivity costs.16 It has also been suggested that ending forced labor could actually fuel economic growth, through demand effects and other impact channels.17

This, combined with the fact that firms that engage in forced labor practices also face significant obstacles due to increasing regulatory pressure and societal scrutiny,18 makes it a pressing issue for investors.

Additionally, unlike other risks, forced labor in the global supply chain is often a hidden issue, one that is extremely difficult for institutional investors to identify and mitigate. Overlooking this risk entirely can lead to financial losses and damage an investor’s reputation, making it worthwhile for institutional investors to screen out companies with high forced labor risk.

How to Gauge a Company’s Ability to Manage Forced Labor Risk

When conducting their due diligence, it may not be feasible for investors to investigate each of the companies they want to include in their portfolio. However, if there is a concern that a company has a high risk of forced labor, engagement meetings and targeted queries through stewardship can be used to assess its understanding and allow investors to gauge the company’s ability to manage those risks.

What is the Severity and Probability of the Company’s Forced Labor Risk?

A company should be able to clearly explain its assessment — which could include desk research, stakeholder consultations, grievance analysis, and social audits — of forced labor risk to investors, in terms of both severity and probability, as well as how it relates to their business operations.

Some companies, such as Nestlé, choose to release dedicated reports on their findings, enabling them to present both identified risks and analysis, as well as mitigation strategies.19 Where this is not practical, companies can also integrate the information into their annual sustainability report.

Forced labor can manifest in various forms, and overlooking or downplaying forced labor issues, including those that some may consider to be less severe, can have significant repercussions for a company.

This includes operational risks, with production disruptions occurring as suppliers face import bans, making it difficult for a company to source alternatives. There are also regulatory risks (although enforcement varies) and each of the 180 countries that have ratified the ILO Forced Labor Convention20 have legal frameworks in place to prohibit forced labor. As a result, employers can face criminal charges, imprisonment, and severe financial consequences. More progressive laws, such as Germany’s Supply Chain Due Diligence Act21 and Canada’s Bill S-211,22 impose financial penalties on companies that fail to identify forced labor risks in their supply chains.

Despite the potential operational and regulatory repercussions, reputational damage is often the most severe consequence. Once a company is associated with forced labor, rebuilding its reputation can take years.

What Are the Root Causes of Forced Labor Within the Company’s Supply Chain?

Companies may exhibit misplaced confidence, assuming that forced labor is unlikely to happen within their supply chains. This may reflect a lack of knowledge, which could potentially lead to insufficient preventative measures being implemented. Instead, companies should be able to elaborate on the root causes of forced labor that are relevant to their businesses.

The root causes of forced labor in the supply chain tend to fall into three categories:

- Demand-side risk factors, such as a company’s pressure on suppliers concerning price, cost, and speed of production.

- Supply-side risk factors, which encompasses poverty, low educational levels, and migration.

- Institutional factors, such as a lack of laws to protect workers and the poor enforcement of existing laws.23

Companies rarely recognize their own purchasing practices as a risk factor, which can lead suppliers to cut corners, at the expense of workers’ rights.

What Do the Company’s Commitments and Remediation Plans Look Like?

Companies should be able to share their commitments and plans for remediation if the above risks become a reality. By having commitments and plans in place, a company shows that it understands that failing to prevent forced labor comes with significant costs. And these costs should incentivize companies to proactively prevent the risks of forced labor.

Forced Labor Indicators

Morningstar Sustainalytics’ ESG Risk Rating provides essential data for institutional investors seeking to evaluate companies exposed to systemic forced labor risks in their supply chains, particularly those with weak management systems to address these issues.

For example, the indicator covering the scope of social supplier standards examines a company’s commitment to preventing human rights violations within its supply chain. This indicator assesses whether a company has adequate standards to combat forced labor, but also considers other related factors such as working hours, living conditions, and wages. These factors can signal forced labor risks, as reported by the ILO. In our Sustainalytics Risk Ratings universe, around 50% have a social supply chain standard in place.

Figure 1 shows that of the companies with a social supply chain standard, 35% are assessed as very weak. At the other end of the spectrum, 27% are considered very strong, while 24% are adequate.

Figure 1. Strength of Companies' Assessment for Scope of Social Supplier Standards

Source: Morningstar Sustainalytics. For informational purposes only.

Note: Data as of June 19, 2025. Analysis of 8,460 public companies in Sustainalytics’ ESG Risk Ratings universe that are assessed for scope of social supplier standards.

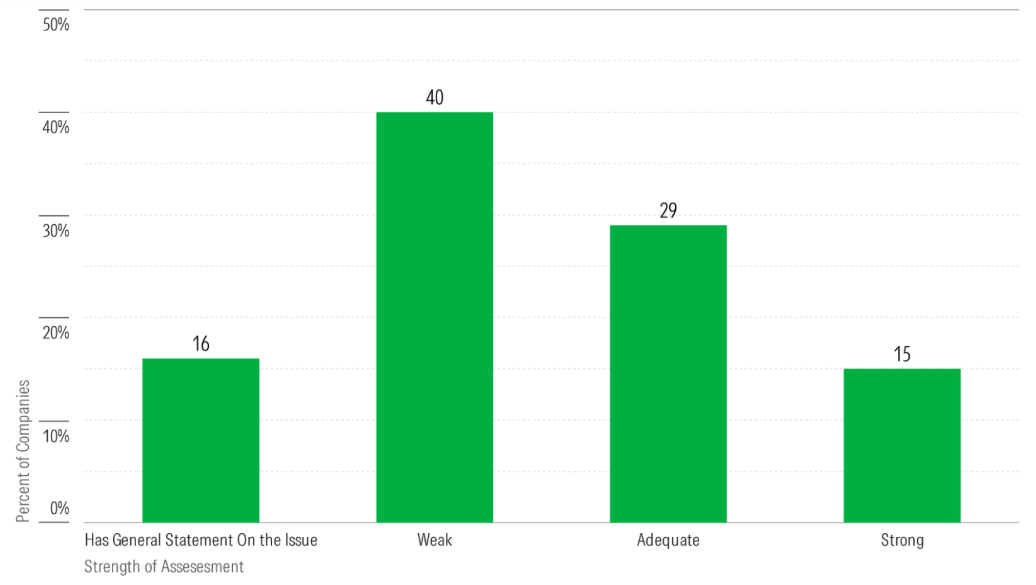

Another indicator on human rights policies is used to evaluate whether a company commits to conduct risk assessments and provide access to remedy. In our Sustainalytics Risk Ratings universe, about 10% of companies have a policy in place, or at minimum, a general statement addressing the issue. For those with a policy, our analysis reveals that the majority of companies (40%) have a weak human rights policy (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Strength of Companies' Human Rights Policies

Source: Morningstar Sustainalytics. For informational purposes only.

Note: Data as of June 19, 2025. Analysis of 1,671 public companies in Sustainalytics’ ESG Risk Ratings universe that are assessed for human rights policies.

For investors, prioritizing companies with a strong understanding of the severity, probability, and root causes of forced labor within their supply chains will help ensure alignment with ethical standards and global regulations, while also mitigating potential financial and reputational risks. Targeted engagement can allow investors to effectively gauge companies' understanding and ability to manage forced labor risks, enabling investors to make more informed decisions that promote accountability, support human rights, and contribute to the broader pursuit of sustainability.

References

- A version of this article originally appeared in Morningstar Sustainalytics' Global Standards Engagement: 2024 Q4 Report.

- International Labour Organization. 2024. “What Is Forced Labour? | International Labour Organization.” ILO.org. January 28, 2024. https://www.ilo.org/topics/forced-labour-modern-slavery-and-trafficking-persons/what-forced-labour.

- International Labour Organization. 1930. C029 - Forced Labour Convention, 1930 (No. 29). https://normlex.ilo.org/dyn/nrmlx_en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::P12100_ILO_CODE:C029.

- International Labour Organization. 1957. C105 - Abolition of Forced Labour Convention, 1957 (No. 105). https://normlex.ilo.org/dyn/nrmlx_en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO:12100:P12100_INSTRUMENT_ID:312250:NO.

- The European Parliament. 2024. REGULATION of the EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT and of the COUNCIL on Prohibiting Products Made with Forced Labour on the Union Market and Amending Directive (EU) 2019/1937. https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/PE-67-2024-INIT/en/pdf.

- UK Public General Acts. 2015. Modern Slavery Act 2015: 2015 Chapter 30. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2015/30/introduction.

- Bureau of International Labor Affairs. 2024. “Labor Rights and the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) | U.S. Department of Labor.” Dol.gov. 2024. https://www.dol.gov/agencies/ilab/our-work/trade/labor-rights-usmca.

- U.S. Customs and Border Protection. 2025. “Withhold Release Orders and Findings Dashboard.” CBP.gov. https://www.cbp.gov/trade/forced-labor/withhold-release-orders-and-findings.

- U.S. Customs and Border Protection. 2025. “Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act.” CBP.gov. https://www.cbp.gov/trade/forced-labor/UFLPA.

- State of California Department of Justice. 2015. “The California Transparency in Supply Chains Act.” State of California - Department of Justice - Office of the Attorney General. March 31, 2015. https://oag.ca.gov/SB657.

- International Labour Organisation. 2022. “Global Estimates of Modern Slavery Forced Labour and Forced Marriage”. ILO.org. Published in September 2022. https://www.ilo.org/sites/default/files/wcmsp5/groups/public/%40ed_norm/%40ipec/documents/publication/wcms_854733.pdf.

- Ibid

- International Labour Organisation. 2022. “Global Estimates of Modern Slavery Forced Labour and Forced Marriage”. ILO.org. Published in September 2022. https://www.ilo.org/sites/default/files/wcmsp5/groups/public/%40ed_norm/%40ipec/documents/publication/wcms_854733.pdf.

- Walk Free Foundation. 2023. “The Global Slavery Index 2023.” Walkfree.org. Published in 2023. https://cdn.walkfree.org/content/uploads/2023/05/17114737/Global-Slavery-Index-2023.pdf.

- The Bureau of International Labor Affairs “List of Goods Produced by Child Labour or Forced Labor”. US Department of Labor. Accessed April 28, 2025. https://www.dol.gov/agencies/ilab/reports/child-labor/list-of-goods.

- Andrew Wallis, “Investing in the Eradication of Forced Labour: A Smart Economic Strategy,” 2024, https://competentboards.com/investing-in-the-eradication-of-forced-labour-a-smart-economic-strategy/.

- International Labour Organization, “Acting against Forced Labour: An Assessment of Investment Requirements and Economic Benefits : Discussion Paper on the Economics of Forced Labour” (ILO, 2024), https://doi.org/10.54394/TYLO1243.

- “Profits and Poverty: The Economics of Forced Labour” (International Labour Organization, 2014), https://documentation.lastradainternational.org/lsidocs/3050-Profits%20and%20Poverty%20-%20The%20Economics%20of%20Forced%20Labour.pdf.

- Nestlé. 2023. “Nestlé Human Rights Salient Issue Action Plans.” https://www.nestle.com/sites/default/files/2023-02/nestle-salient-issues-action-plans-feb-2023.pdf.

- “Ratifications by Country.” 2015. Ilo.org. 2015. https://normlex.ilo.org/dyn/nrmlx_en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:11001:0::NO.

- Ebert, F. Ch., & Francavilla F., & Guarcello L. “Tackling Forced Labour in Supply Chains: The Potential of Trade and Investment Governance,” International Labour Organization. Published in 2023. https://www.ilo.org/media/479516/download.

- Federal Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs. 2021. “CSR - Supply Chain Act.” Www.bmas.de. 2021. https://www.csr-in-deutschland.de/EN/Business-Human-Rights/Supply-Chain-Act/supply-chain-act.html.

- Canada, Public Safety. 2023. “Forced Labour in Canadian Supply Chains.” Www.publicsafety.gc.ca. June 21, 2023. https://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/cnt/cntrng-crm/frcd-lbr-cndn-spply-chns/index-en.aspx.